Baseball and I, we met at Parker Field in Richmond, Virginia in September of ’83. It was a hot, humid night. A thunderstorm loomed in the west, just above the stadium lights.

Alright, most of that isn’t true. I do know that we met at Parker Field, but I have no idea when it was. I don’t even remember Parker Field. It was torn down in 1984 when I was 6, and I’m not that good at remembering things anyhow. Parker Field was the home of the Richmond Braves, Atlanta’s top farm team. Its replacement, The Diamond, opened in 1985 and is still there today. The R-Braves are not.

Since Richmond was the final stop for kids on their way to Atlanta, I saw some great players: Glavine in ’87, Smoltz in ’88, Justice in ’89, Chipper in ’93. I’d later see these same kids on TBS every night. It never really seemed like I had a choice: The Atlanta Braves became my favorite team. By the time I’d moved on from tee ball, I had Dale Murphy posters plastered on my wall. I was mimicking Ozzie Virgil’s catching stance. I was convinced Zane Smith was the best pitcher ever. Remember, though, the Braves sucked for most of the 80s. They were horrible. Really, truly horrible. My friend Jason always made fun of the Braves. And he was a freaking Blue Jays fan.

Since Richmond was the final stop for kids on their way to Atlanta, I saw some great players: Glavine in ’87, Smoltz in ’88, Justice in ’89, Chipper in ’93. I’d later see these same kids on TBS every night. It never really seemed like I had a choice: The Atlanta Braves became my favorite team. By the time I’d moved on from tee ball, I had Dale Murphy posters plastered on my wall. I was mimicking Ozzie Virgil’s catching stance. I was convinced Zane Smith was the best pitcher ever. Remember, though, the Braves sucked for most of the 80s. They were horrible. Really, truly horrible. My friend Jason always made fun of the Braves. And he was a freaking Blue Jays fan.

And then ’91 happened. That’s when baseball and I really hit it off. That’s when we took our relationship to the next level.

(To this day, I hate Kent Hrbek. I still check and see if the Giants or Reds lost, even though it’s been almost 20 years since they were in the NL West together. I’d put Mark Lemke in the Hall of Fame. I think Terry Pendleton deserved that MVP.)

Baseball and I spent a lot of time together in those days. Baseball cards provided me the first opportunity to refine my obsessive organizational skills. I watched Baseball Tonight religiously. Every year in early July, I’d plan out All-Star Game night: The right TV angle, the best position on the couch, dinner, the dessert. I could tell you every team’s opening day lineup. I created each All-Star team in Baseball Stars (SHEFLD of the ‘92 National League team was an absolute monster). I’d watch the Cubs on WGN in the afternoon and then the Braves at night on TBS.

But somewhere along the line, at some point in our relationship, things began to change.

It had nothing to do with The Strike. Strikes happen. It had nothing to do with The Steroids. I would have probably done steroids if I played pro baseball. And it had nothing to do with The All-Star Game Determines the Home Team in the World Series. Oh, I know it’s really stupid, but it’s a small blip on the radar. None of those really pushed baseball and I apart.

There were some little things I started to notice, little pet peeves that I thought our love could overcome. At times, ESPN’s coverage of baseball (everything, really) stumbled into yellow journalism. Joe Morgan, Joe Buck and Tim McCarver made watching baseball almost unbearable. The lack of any sort of competitive balance went from annoying to bothersome to deplorable in a matter of years. The Hall of Fame voting. TBS dropping regular coverage of the Braves. I was sure we could weather those storms.

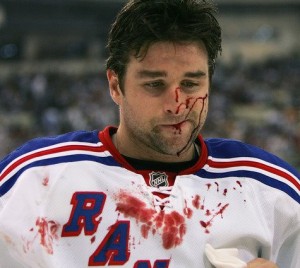

See, I never wanted to admit that I saw the end coming. But my eyes began wandering a bit. I mean, have you seen hockey in HD? I began thinking about others more, thinking about spending more time with football. But I always came back to baseball. This distance between us, it grew in the tiniest of increments, and then one day, I woke up and those little increments had become one giant gulf.

I didn’t seem to know baseball anymore. I couldn’t tell you many opening day lineups. I didn’t know where some free agents had gone. (Jeff Francoeur is on the Royals now? And he was on the Rangers last year?) I can’t tell you the Braves’ 25-man roster right now. I’ve even skipped World Series games. I admit there were World Series games where I didn’t see a single pitch. I saw my friends spending more and more time with baseball and began to feel guilty (yes, I’m talking about you, Wells).

And there was that day, the day when I learned something about baseball that I couldn’t fully live with. On the surface, it didn’t seem like a big deal. But it felt like a big deal: That seedy underbelly of your family-friendly, hometown Minor League Baseball. The way small cities and communities are cowed into giving up the farm for a team that was once the pride of another community. The way these small baseball teams could hold towns hostage. They tell me that, after all, baseball is a business. But that doesn’t really make it any less ugly.

Remember Richmond, where baseball and I met? Allow me to digress. Those very same R-Braves, they moved to Richmond in 1966, the same year the big league Braves moved from Milwaukee to Atlanta. For the next 43 seasons, the R-Braves were Atlanta’s top minor league team. Freaking Dusty Baker played for the R-Braves, that’s how long they’d been around.

The R-Braves were owned by their parent club in Atlanta. They’d seen The Diamond and they knew it was a pit. A giant, sterile, concrete pit. It was old and dated before the first pitch. They came to town, and they told the Richmond, “We want a new stadium. Richmond should build us a new stadium.” (Not an exact quote.)

The R-Braves were owned by their parent club in Atlanta. They’d seen The Diamond and they knew it was a pit. A giant, sterile, concrete pit. It was old and dated before the first pitch. They came to town, and they told the Richmond, “We want a new stadium. Richmond should build us a new stadium.” (Not an exact quote.)

The “…or else” is always understood. When minor league team owners get antsy for a new stadium, they make a trip down to your City Hall, schedule a couple of lunch meetings with your Elected Officials. There is always another city who will build a state-of-the-art, shiny new stadium. And the Richmond VIPs made the decision (or non-decision) to take some time and explore their options. In the end, though, the R-Braves became the Gwinnett Braves after the 2008 season. Go find Gwinnett on a map.

(Postscript: A year later, Richmond got an Eastern League franchise affiliated with… wait for it… the San Francisco Giants.)

Richmonders had been going to R-Braves games for 43 years. LBJ was still President. Richmond was a stalwart of the International League, a five-time champion. But Gwinnett County was willing to put their taxpayers on the hook for a stadium that won’t be paid off until 2038. The taxpayers pay for the facility and its maintenance, the team keeps ticket and concessions revenue.

It’s a good business model for the team. It sucks for everyone else. Head up north and ask Edmonton about Nolan Ryan moving the city’s team to Round Rock, Texas. Ask Ottawa about the Lynx. Next year, ask Yakima, Washington and Kinston, North Carolina. Hell, go ask the fine people of Portland, Oregon: They’ve made getting screwed by baseball franchises into an art form.

I’ll paraphrase Henry Hill from Goodfellas for the kids: Screw you, pay me.

So, what does all of this have to do with me and baseball? We all grow up and with age comes a little perspective. A reshuffling of priorities. Perhaps a little touch of cynicism. I wasn’t too old to love baseball, I just didn’t love it the same way. I could no longer buy into the idea that baseball should be as loyal to its fans as its fans are to it. The fans always lose that fight. And that’s when baseball and I went down to the courthouse and filed. Irreconcilable differences.

My baseball cards, they’re in a box in the basement. I don’t get (that) mad anymore when I think about how Dale Murphy isn’t in the Hall of Fame. I own a Minnesota Twins t-shirt. And I’ve been known to wear it.

Some days I do miss what baseball and I had. And don’t misunderstand me, baseball and I still talk. Some nights the wife and the kid, we all get together and spend some time with baseball, watching the Braves when they’re on. We watch Dan Uggla ground into double plays and Derek Lowe throw his 88 mph fastball and I think back to the Braves of the 1980s. I follow Dale Murphy’s Twitter feed. I’m counting down the days until I can play catch with my son.

Baseball and I, we still have those memories. A Sunday game at Camden Yards. That 1995 World Series. McGwire’s home run (despite all that came later). Miserably hot Spring Training games in Arizona. And I still plan on creating new memories with baseball: There are many more stadiums to visit, many more teams to see. And I’ll always love the game’s history: The cowboy days of the 1800s, the turn of the century chaos, etc.

But our relationship, it’ll never be the same as it was.

See, this is a foreign concept for D.C. sports fans, especially Capitals fans. For decades, we watched stars take less money to avoid the Beltway.

See, this is a foreign concept for D.C. sports fans, especially Capitals fans. For decades, we watched stars take less money to avoid the Beltway. The fan base was loyal and motivated—sure, it wasn’t Toronto or Boston or even St. Louis, but surely D.C. was a better stop than, say, a dying Minnesota North Stars franchise, the remote village of Quebec City (to non-francophones, anyway) or Hartford, the insurance capital of America.

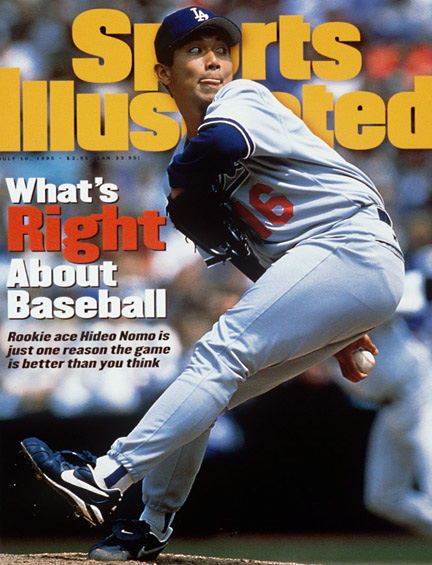

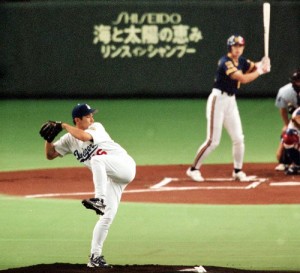

The fan base was loyal and motivated—sure, it wasn’t Toronto or Boston or even St. Louis, but surely D.C. was a better stop than, say, a dying Minnesota North Stars franchise, the remote village of Quebec City (to non-francophones, anyway) or Hartford, the insurance capital of America. Nomo Mania began in the 1995 season, when he splashed onto the Major League scene with the Los Angeles Dodgers, seemingly out of nowhere, after a bitter contract dispute with the Kintetsu Buffaloes of the Pacific League in Japan. Mesmerizing crowds and bewildering opposing batters at every ballpark with his never-before-seen “tornado” windup style, he finished the season with an impressive résumé, leading the league in strikeouts, a 13-6 record and a 2.54 ERA. And let’s not forget he was the starting pitcher for the National League in the All-Star Game. His performance was even more impressive the following season, going 16-11 and capping the year off with a no-hitter at Denver’s Coors Field, the hitter’s paradise. All these numbers, however, don’t begin to tell the story of Nomo, whose legacy, while paling in comparison to that of Jackie Robinson, warrants a discussion as a future Hall of Fame member for his contributions to the game of baseball as a whole.

Nomo Mania began in the 1995 season, when he splashed onto the Major League scene with the Los Angeles Dodgers, seemingly out of nowhere, after a bitter contract dispute with the Kintetsu Buffaloes of the Pacific League in Japan. Mesmerizing crowds and bewildering opposing batters at every ballpark with his never-before-seen “tornado” windup style, he finished the season with an impressive résumé, leading the league in strikeouts, a 13-6 record and a 2.54 ERA. And let’s not forget he was the starting pitcher for the National League in the All-Star Game. His performance was even more impressive the following season, going 16-11 and capping the year off with a no-hitter at Denver’s Coors Field, the hitter’s paradise. All these numbers, however, don’t begin to tell the story of Nomo, whose legacy, while paling in comparison to that of Jackie Robinson, warrants a discussion as a future Hall of Fame member for his contributions to the game of baseball as a whole. While we can’t give Nomo all the credit for the globalization of baseball in the last decade, the success that he enjoyed encouraged 42 other Japanese players to successfully make their way to the Majors since then. This alone speaks volumes. Sure, Ichiro might have ended up playing in the Majors anyway, but perhaps not as early as 2001. And Nomo’s success certainly influenced general managers across the MLB to look outside of the U.S. to not only Japan, but other Asian countries as well. The infusion of Latin and Asian players into the Majors in the last 15 years, along with the additional revenue the MLB has generated with its globalization initiatives, must, at least in part, be credited to him.

While we can’t give Nomo all the credit for the globalization of baseball in the last decade, the success that he enjoyed encouraged 42 other Japanese players to successfully make their way to the Majors since then. This alone speaks volumes. Sure, Ichiro might have ended up playing in the Majors anyway, but perhaps not as early as 2001. And Nomo’s success certainly influenced general managers across the MLB to look outside of the U.S. to not only Japan, but other Asian countries as well. The infusion of Latin and Asian players into the Majors in the last 15 years, along with the additional revenue the MLB has generated with its globalization initiatives, must, at least in part, be credited to him. Before I continue, it’s important I disclose to you that I hate Michael Vick as much as you can hate someone you’ve never met.

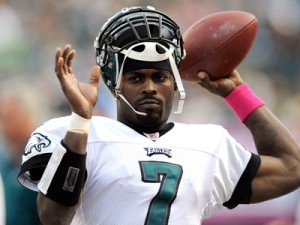

Before I continue, it’s important I disclose to you that I hate Michael Vick as much as you can hate someone you’ve never met. But Vick’s actions aren’t simple. They require analysis way above my pay grade. It’s not as easy as evoking “they’re just dogs.” 99% of those who’ve uttered “they’re just dogs” would not stand by and allow something like dog-baiting to occur in their presence. Vick didn’t simply participate in dogfighting. He led and financed an interstate crime syndicate, and he hosted it on his own property. He hung and drowned dogs who “underperformed.” It’s not an issue of culture—that defense is as racist as it is ridiculous. It’s not an issue of mankind’s dominion over animals. It’s a question about the very value of life. I truly believe that Vick’s lack of respect for life extends to humans. I truly believe that Vick will be forever incapable of understanding the gravity of his actions.

But Vick’s actions aren’t simple. They require analysis way above my pay grade. It’s not as easy as evoking “they’re just dogs.” 99% of those who’ve uttered “they’re just dogs” would not stand by and allow something like dog-baiting to occur in their presence. Vick didn’t simply participate in dogfighting. He led and financed an interstate crime syndicate, and he hosted it on his own property. He hung and drowned dogs who “underperformed.” It’s not an issue of culture—that defense is as racist as it is ridiculous. It’s not an issue of mankind’s dominion over animals. It’s a question about the very value of life. I truly believe that Vick’s lack of respect for life extends to humans. I truly believe that Vick will be forever incapable of understanding the gravity of his actions. Just a few days ago, Nike signed Vick to an endorsement deal four years after they severed ties with him. Forgive and forget? Nike weighed the pros and the cons and they came to the conclusion that it makes business sense to have Vick out there on their behalf. Nike is banking on the fact that those of us who buy their products have forgiven by now (or don’t care). Nike can take the hit from those who, like me, will never buy another Nike product.

Just a few days ago, Nike signed Vick to an endorsement deal four years after they severed ties with him. Forgive and forget? Nike weighed the pros and the cons and they came to the conclusion that it makes business sense to have Vick out there on their behalf. Nike is banking on the fact that those of us who buy their products have forgiven by now (or don’t care). Nike can take the hit from those who, like me, will never buy another Nike product. I don’t think anyone has forgotten, though. Vick’s name will be forever synonymous with dogfighting. In the end, it seems that forgiving is more important and easier than forgetting. Forgiving is especially easy when it accompanies winning. Winning is very powerful force. Kobe Bryant has been forgiven since his rape charges in 2003. The eight years have helped, but the Lakers’ two championships really helped. Ray Lewis led the Ravens to a win in Super Bowl XXXV and was named its MVP. This was a year after his involvement (to whatever extent) in the stabbing deaths of two people. His past transgressions might even be forgotten at this point. When we talk about Lewis now, we talk about his place in the pantheon of football players, not his past.

I don’t think anyone has forgotten, though. Vick’s name will be forever synonymous with dogfighting. In the end, it seems that forgiving is more important and easier than forgetting. Forgiving is especially easy when it accompanies winning. Winning is very powerful force. Kobe Bryant has been forgiven since his rape charges in 2003. The eight years have helped, but the Lakers’ two championships really helped. Ray Lewis led the Ravens to a win in Super Bowl XXXV and was named its MVP. This was a year after his involvement (to whatever extent) in the stabbing deaths of two people. His past transgressions might even be forgotten at this point. When we talk about Lewis now, we talk about his place in the pantheon of football players, not his past. It has been said that he paid his “debt to society.” I’m not sure what that means. But obviously many people do. If he continues to play as he did in the 2010 season, if by some miracle the Eagles win a Super Bowl, the percentage of people who forgive will increase. That’s how it works, for better or for worse.

It has been said that he paid his “debt to society.” I’m not sure what that means. But obviously many people do. If he continues to play as he did in the 2010 season, if by some miracle the Eagles win a Super Bowl, the percentage of people who forgive will increase. That’s how it works, for better or for worse. To be honest, I can’t pinpoint a single game or moment that made me a Mets fan. Growing up in Long Island, long summer days were spent playing baseball and home run derby at the park. We’d emulate our favorite players’ batting stances and pitching motions. In particular, I was infamous for my Jeff Innis sidearm delivery impression, and my Daryl Strawberry silky smooth swing was uncanny. My father was particularly enamored with the ‘86 Mets. He loved Keith Hernandez and Gary Carter. We spent many hazy summer nights watching the Mets on TV after he’d get home from work. I loved it when he told me stories of that season, and how the they were unlike any other team he’d ever watched. Shea Stadium in nearby Flushing was a mere 30 minute drive from home, so we’d go to at least one game a season. Combine all the aforementioned factors, and unfortunately, a Mets fan was born.

To be honest, I can’t pinpoint a single game or moment that made me a Mets fan. Growing up in Long Island, long summer days were spent playing baseball and home run derby at the park. We’d emulate our favorite players’ batting stances and pitching motions. In particular, I was infamous for my Jeff Innis sidearm delivery impression, and my Daryl Strawberry silky smooth swing was uncanny. My father was particularly enamored with the ‘86 Mets. He loved Keith Hernandez and Gary Carter. We spent many hazy summer nights watching the Mets on TV after he’d get home from work. I loved it when he told me stories of that season, and how the they were unlike any other team he’d ever watched. Shea Stadium in nearby Flushing was a mere 30 minute drive from home, so we’d go to at least one game a season. Combine all the aforementioned factors, and unfortunately, a Mets fan was born.

There are few better moments in all of sports better than waiting for a crucial pitch to be delivered late in October. If the Mets were to break the curse of being the Mets, this was the perfect moment. There was no one I’d rather have up at the plate than the next batter, Carlos Beltran. 41 homeruns, 116 RBI, All-Star, Gold Glove winner, Silver Slugger winner. This was why the Mets shelled out the big bucks for the quiet centerfielder. First pitch, strike 1. Second pitch, strike 2. I looked at my best friend and fellow Mets fan. No words were needed. As I took a deep gulp and tried to compose myself for what was to follow, an undeniably ominous feeling crept through my bones. Ya gotta believe, they say. Wainwright would pause at the top of the mound for what seemed like an eternity. He then delivered one of the filthiest, nastiest curveballs I’ve ever seen. As the ball dropped 12-6 on the outside corner of the plate and into the catcher’s mitt, Beltran still had his bat on his shoulders. I knew my dreams were shattered. Our clean-up hitter, our big home run man, our hope to break this curse, didn’t even swing the bat. It was all over. I stood stoically as some Yankees fans came over to offer a kind word. It’s hard to recall what they said exactly because the whole bar had become eerily silent, and everything around me had become a blur. Absolutely gutted. Then rage. He didn’t even swing the bat! Just like that, one pitch and order in the universe was restored. The Mets disappointed yet again.

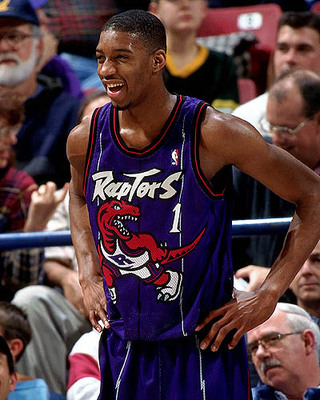

There are few better moments in all of sports better than waiting for a crucial pitch to be delivered late in October. If the Mets were to break the curse of being the Mets, this was the perfect moment. There was no one I’d rather have up at the plate than the next batter, Carlos Beltran. 41 homeruns, 116 RBI, All-Star, Gold Glove winner, Silver Slugger winner. This was why the Mets shelled out the big bucks for the quiet centerfielder. First pitch, strike 1. Second pitch, strike 2. I looked at my best friend and fellow Mets fan. No words were needed. As I took a deep gulp and tried to compose myself for what was to follow, an undeniably ominous feeling crept through my bones. Ya gotta believe, they say. Wainwright would pause at the top of the mound for what seemed like an eternity. He then delivered one of the filthiest, nastiest curveballs I’ve ever seen. As the ball dropped 12-6 on the outside corner of the plate and into the catcher’s mitt, Beltran still had his bat on his shoulders. I knew my dreams were shattered. Our clean-up hitter, our big home run man, our hope to break this curse, didn’t even swing the bat. It was all over. I stood stoically as some Yankees fans came over to offer a kind word. It’s hard to recall what they said exactly because the whole bar had become eerily silent, and everything around me had become a blur. Absolutely gutted. Then rage. He didn’t even swing the bat! Just like that, one pitch and order in the universe was restored. The Mets disappointed yet again. Tracy Lamar McGrady, Jr. was drafted 9th overall by the Toronto Raptors in the 1997 NBA Draft. He came straight out of high school and mainly played a reserve role in his first two seasons. A year after T-Mac’s arrival, the Raptors drafted his cousin Vince Carter with the 5th pick: The high flying duo instantly built expectations for the Canadian franchise. They finally led the Raptors to a playoff berth in 2000 only to get swept by the Knicks in the first round. Then, in order to escape the shadow of his older cousin, he forced the hand of the Raptors into a sign-and-trade that sent him to the Orlando Magic.

Tracy Lamar McGrady, Jr. was drafted 9th overall by the Toronto Raptors in the 1997 NBA Draft. He came straight out of high school and mainly played a reserve role in his first two seasons. A year after T-Mac’s arrival, the Raptors drafted his cousin Vince Carter with the 5th pick: The high flying duo instantly built expectations for the Canadian franchise. They finally led the Raptors to a playoff berth in 2000 only to get swept by the Knicks in the first round. Then, in order to escape the shadow of his older cousin, he forced the hand of the Raptors into a sign-and-trade that sent him to the Orlando Magic. But T-Mac had Yao: That should mean something, right? But those Rockets fans who’ve obsessed over our pitfalls know better. There’s no need to discuss Yao’s fragility as that’s deserving of its own article. Yao was (and still is) the Rockets’ cash cow, whether the organization admits it or not. Retaining Yao, even into next year regardless of how much of a liability his injuries have become, is important if only because Yao is a significant financial asset. But Yao’s body and game were never meant to be paired with someone like T-Mac. In his prime, T-Mac represented an ideal NBA body: 6’9″ with a 7’3″ wingspan, 42-inch vertical jump, 235 pounds with only 8% body fat and ran the 40-yard dash in less than 4.5 seconds. He represented the perfect combination of height, weight, speed and strength to be successful in the league—a build like LeBron but with T-Mac’s quickness making up for his lack of similar upper body strength. This quickness suited him a fast-paced system, not one that has to have a half-court set with Yao. In addition, Yao’s game has always been easily neutralized: Too uncoordinated to catch quick passes, too tall to have true success with his back facing the basket, too slow and un-athletic to defend against players that would front him. The list goes on. I’m a fan of Yao only because the man always says and does the right thing and has a lot of heart. But heart only gets you so far. I’ve never met anyone who agreed that the two superstars’ games complemented each other, but everyone agreed that they were indeed “superstars” and would bring in the “kwan” and “show the Rockets the money.” (Jerry Maguire quotes seem quite fitting when discussing money and heart together.) The Rockets would’ve had more success if they had traded Yao for versatile and mobile big men, or if they had traded T-Mac for knock down shooters and defenders (something that Mark Cuban would have done without hesitation)—but the Rockets held onto their “superstars” as money in the pocket instead of building a better ball club to advance to the second round and beyond. The failures of Team USA basketball in the early 2000s have taught us that you can’t just stick a bunch of good players together and expect to win. They have to gel and complement each other. Let’s put this into a statistical perspective: Until the end of the 2007 season, the Rockets won 59% of games with Yao on the floor and 70% without.

But T-Mac had Yao: That should mean something, right? But those Rockets fans who’ve obsessed over our pitfalls know better. There’s no need to discuss Yao’s fragility as that’s deserving of its own article. Yao was (and still is) the Rockets’ cash cow, whether the organization admits it or not. Retaining Yao, even into next year regardless of how much of a liability his injuries have become, is important if only because Yao is a significant financial asset. But Yao’s body and game were never meant to be paired with someone like T-Mac. In his prime, T-Mac represented an ideal NBA body: 6’9″ with a 7’3″ wingspan, 42-inch vertical jump, 235 pounds with only 8% body fat and ran the 40-yard dash in less than 4.5 seconds. He represented the perfect combination of height, weight, speed and strength to be successful in the league—a build like LeBron but with T-Mac’s quickness making up for his lack of similar upper body strength. This quickness suited him a fast-paced system, not one that has to have a half-court set with Yao. In addition, Yao’s game has always been easily neutralized: Too uncoordinated to catch quick passes, too tall to have true success with his back facing the basket, too slow and un-athletic to defend against players that would front him. The list goes on. I’m a fan of Yao only because the man always says and does the right thing and has a lot of heart. But heart only gets you so far. I’ve never met anyone who agreed that the two superstars’ games complemented each other, but everyone agreed that they were indeed “superstars” and would bring in the “kwan” and “show the Rockets the money.” (Jerry Maguire quotes seem quite fitting when discussing money and heart together.) The Rockets would’ve had more success if they had traded Yao for versatile and mobile big men, or if they had traded T-Mac for knock down shooters and defenders (something that Mark Cuban would have done without hesitation)—but the Rockets held onto their “superstars” as money in the pocket instead of building a better ball club to advance to the second round and beyond. The failures of Team USA basketball in the early 2000s have taught us that you can’t just stick a bunch of good players together and expect to win. They have to gel and complement each other. Let’s put this into a statistical perspective: Until the end of the 2007 season, the Rockets won 59% of games with Yao on the floor and 70% without. Never did I dream that we would acquire both of you. Never did I dream that it would quickly turn into a nightmare. It was elating in the moment, though, watching you guys flip a puck to see who would wear #23.

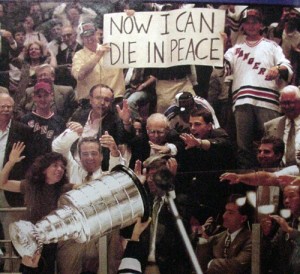

Never did I dream that we would acquire both of you. Never did I dream that it would quickly turn into a nightmare. It was elating in the moment, though, watching you guys flip a puck to see who would wear #23. Still, after Jagr left you were named captain. Rightly so. You were fulfilling the dream of millions in the NY Metro area—the entire sports fan world, really—to play for the team you grew up rooting for. In explaining your departure from Buffalo you explained to the fans that it was like a kid from Rochester being offered a chance to play for the Sabres. You had to take it. Just that fact made you instantly beloved by fans of a certain generation (mine, born in the early 80s and older), though your diminishing skills and silent, lead-by-example style did nothing to impress younger fans who were not sated by the Stanley Cup win in 1994 as my generation was. They could not identify with the famous “Now I Can Die in Peace” banner held up that night. They didn’t witness a cup.

Still, after Jagr left you were named captain. Rightly so. You were fulfilling the dream of millions in the NY Metro area—the entire sports fan world, really—to play for the team you grew up rooting for. In explaining your departure from Buffalo you explained to the fans that it was like a kid from Rochester being offered a chance to play for the Sabres. You had to take it. Just that fact made you instantly beloved by fans of a certain generation (mine, born in the early 80s and older), though your diminishing skills and silent, lead-by-example style did nothing to impress younger fans who were not sated by the Stanley Cup win in 1994 as my generation was. They could not identify with the famous “Now I Can Die in Peace” banner held up that night. They didn’t witness a cup. You and Ryan Callahan did Ranger fans proud at the Vancouver Olympics, but we wondered why you lacked that same drive when you played for us. We saw the same Cally on the ice at the Garden as we saw in Vancouver,, but you were different, like that jersey mattered more to you than the Ranger jersey. I’m sure it didn’t, but it felt that way at times.

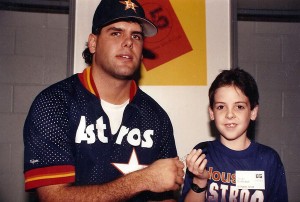

You and Ryan Callahan did Ranger fans proud at the Vancouver Olympics, but we wondered why you lacked that same drive when you played for us. We saw the same Cally on the ice at the Garden as we saw in Vancouver,, but you were different, like that jersey mattered more to you than the Ranger jersey. I’m sure it didn’t, but it felt that way at times. Ken Caminiti was the greatest 3rd baseman I’d ever seen. Maybe he wasn’t, but when you’re nine, you have a distorted frame of reference. All I knew was that he could stop a bullet down the line and fire off a fastball to first that would have made Nolan Ryan blush. Yeah, and he swung a mean stick. But more than that, he was a good guy, and he played for my team. Bagwell, Biggio, Gonzalez, they all were. How could they not be? I cheered for them, I wore a smile for weeks after I got one of them to sign a ball for me, and I religiously watched them at night. Even after Caminiti was traded to San Diego, he was still a Houston Astro for me. Being one was more than a jersey; he just happened to play elsewhere. I had no perspective at that age about the “business” end of sports. It was so much more than just that.

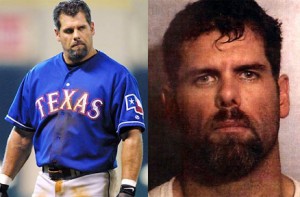

Ken Caminiti was the greatest 3rd baseman I’d ever seen. Maybe he wasn’t, but when you’re nine, you have a distorted frame of reference. All I knew was that he could stop a bullet down the line and fire off a fastball to first that would have made Nolan Ryan blush. Yeah, and he swung a mean stick. But more than that, he was a good guy, and he played for my team. Bagwell, Biggio, Gonzalez, they all were. How could they not be? I cheered for them, I wore a smile for weeks after I got one of them to sign a ball for me, and I religiously watched them at night. Even after Caminiti was traded to San Diego, he was still a Houston Astro for me. Being one was more than a jersey; he just happened to play elsewhere. I had no perspective at that age about the “business” end of sports. It was so much more than just that. And then it happened. Eight years and many confessions later, Caminiti was dead. I had lost a part of me. I had lost my innocence. Superheroes weren’t supposed to die. Or have a cocaine habit. Or cheat. Watching his fall was painful. I poured over his Sports Illustrated story and tales of steroid abuse. All those stats I had memorized now had a nice, big asterisk.

And then it happened. Eight years and many confessions later, Caminiti was dead. I had lost a part of me. I had lost my innocence. Superheroes weren’t supposed to die. Or have a cocaine habit. Or cheat. Watching his fall was painful. I poured over his Sports Illustrated story and tales of steroid abuse. All those stats I had memorized now had a nice, big asterisk. Then, in 2004, I began dating a man who was an ardent Chicago Bears fan. At the beginning of our relationship, it was easy to avoid the games: Adam would be busy on Sunday afternoons, and I’d find something else to do. Football gave me an excuse to have boozy brunches with my ladies. (Though, come to think of it, I probably didn’t need an excuse.) Once we began cohabiting, though, the NFL was much harder to avoid. Initially, we struck a bargain: If I received physical attention in the form of cuddling, I’d watch the games with him. Then the bargain extended to the bar: I’d only come if at least one of my beers was purchased for me and there were wings. Inadvertently, I started learning about the game. At the beginning, I would make up meanings for the call gestures: holding wasn’t holding, it was fisting; that’s not a false start, but rather a sign for the bossa nova (time for a dance break)! The discovery of a new favorite sound made the game even more entertaining: When the rival team attempted a field goal and missed by hitting the posts, the resounding klongggggggg was pure pleasure. Eventually, I did actually accumulate some knowledge, though I’m still nowhere near the level of my male friends who make the calls before the referees do.

Then, in 2004, I began dating a man who was an ardent Chicago Bears fan. At the beginning of our relationship, it was easy to avoid the games: Adam would be busy on Sunday afternoons, and I’d find something else to do. Football gave me an excuse to have boozy brunches with my ladies. (Though, come to think of it, I probably didn’t need an excuse.) Once we began cohabiting, though, the NFL was much harder to avoid. Initially, we struck a bargain: If I received physical attention in the form of cuddling, I’d watch the games with him. Then the bargain extended to the bar: I’d only come if at least one of my beers was purchased for me and there were wings. Inadvertently, I started learning about the game. At the beginning, I would make up meanings for the call gestures: holding wasn’t holding, it was fisting; that’s not a false start, but rather a sign for the bossa nova (time for a dance break)! The discovery of a new favorite sound made the game even more entertaining: When the rival team attempted a field goal and missed by hitting the posts, the resounding klongggggggg was pure pleasure. Eventually, I did actually accumulate some knowledge, though I’m still nowhere near the level of my male friends who make the calls before the referees do. My path to being interested in sports on any level hit each of these marks. My good friend, Danny, worked for a time on the Major League Soccer website. That, combined with a trip to Adam’s Chicago family, gave the boys a perfect opportunity to introduce me to soccer. (I still think it should be called football, as it is everywhere else in the world and is far more accurate.) As I said before, what I knew of soccer extended to the tips of my braids, but they were committed to changing that. And what better way than to take me to a live game? Not just any live game, though: The opening of Chicagoland area’s Toyota Park in June 2006. When it comes to sports, live games are good, opening days are better and grand openings are best—talk about fanfare! During the game they gave me insights and explanations on how the game was played (much the same way they would on Sunday afternoons at football bars). Our seats were not the best in the arena, but from where we were sitting I could see many of the players and quickly developed a crush on Chicago Fire’s lanky

My path to being interested in sports on any level hit each of these marks. My good friend, Danny, worked for a time on the Major League Soccer website. That, combined with a trip to Adam’s Chicago family, gave the boys a perfect opportunity to introduce me to soccer. (I still think it should be called football, as it is everywhere else in the world and is far more accurate.) As I said before, what I knew of soccer extended to the tips of my braids, but they were committed to changing that. And what better way than to take me to a live game? Not just any live game, though: The opening of Chicagoland area’s Toyota Park in June 2006. When it comes to sports, live games are good, opening days are better and grand openings are best—talk about fanfare! During the game they gave me insights and explanations on how the game was played (much the same way they would on Sunday afternoons at football bars). Our seats were not the best in the arena, but from where we were sitting I could see many of the players and quickly developed a crush on Chicago Fire’s lanky  There are people in Kentucky who will threaten bloody murder upon hearing the words “Christian” and “Laettner” one after another. Because

There are people in Kentucky who will threaten bloody murder upon hearing the words “Christian” and “Laettner” one after another. Because