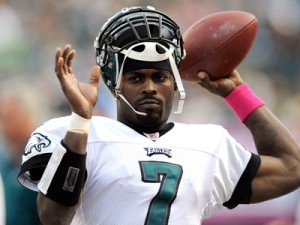

A few months ago, the NFL handed out its awards for the 2010 season. One of those awards went to Michael Vick, who was named the Comeback Player of the Year by the Associated Press. On the surface, it makes sense: The previous season, he completed 6 passes for 86 yards as the backup to Donavan McNabb. Before that, he hadn’t played since 2006. This past season, however, he threw for over 3,000 yards, rushed for another 700 or so and had a total of 30 touchdowns. I watch a lot of NFL, and there’s no doubt this was the most dramatically pronounced improvement of any player in the league.

Before I continue, it’s important I disclose to you that I hate Michael Vick as much as you can hate someone you’ve never met.

Before I continue, it’s important I disclose to you that I hate Michael Vick as much as you can hate someone you’ve never met.

I realize that sounds pretty harsh. But I personally believe that animals have intrinsic value, that they do not exist solely to serve as means for our ends. That means all of the following: I find any testing done on animals deplorable, regardless of the real or perceived benefits to mankind; I consider the very idea of purchasing an animal—any animal—offensive; I believe the very idea of hunting and fishing as “sport” is a blight on mankind; and I believe Gandhi said it best when he remarked, “The greatness of a nation and its moral progress can be judged by the way its animals are treated.”

I’m well aware that these views may verge on heresy for some. I’m fine with that. I don’t hold animals in higher regard than humans, and nothing I say about Vick would suggest otherwise.

But Vick’s actions aren’t simple. They require analysis way above my pay grade. It’s not as easy as evoking “they’re just dogs.” 99% of those who’ve uttered “they’re just dogs” would not stand by and allow something like dog-baiting to occur in their presence. Vick didn’t simply participate in dogfighting. He led and financed an interstate crime syndicate, and he hosted it on his own property. He hung and drowned dogs who “underperformed.” It’s not an issue of culture—that defense is as racist as it is ridiculous. It’s not an issue of mankind’s dominion over animals. It’s a question about the very value of life. I truly believe that Vick’s lack of respect for life extends to humans. I truly believe that Vick will be forever incapable of understanding the gravity of his actions.

But Vick’s actions aren’t simple. They require analysis way above my pay grade. It’s not as easy as evoking “they’re just dogs.” 99% of those who’ve uttered “they’re just dogs” would not stand by and allow something like dog-baiting to occur in their presence. Vick didn’t simply participate in dogfighting. He led and financed an interstate crime syndicate, and he hosted it on his own property. He hung and drowned dogs who “underperformed.” It’s not an issue of culture—that defense is as racist as it is ridiculous. It’s not an issue of mankind’s dominion over animals. It’s a question about the very value of life. I truly believe that Vick’s lack of respect for life extends to humans. I truly believe that Vick will be forever incapable of understanding the gravity of his actions.

With all of that out of the way, we arrive at the question that was posed recently here at Perfecting the Upset: Do we, the fans, forgive and forget athletes’ transgressions too easily?

The short answer? Yes. Absolutely. In general terms, athletes are held to a lower standard than the rest of us. To some extent, we expect athletes to screw up: Drunk driving, domestic violence, hanging out with the wrongest of crowds at the wrongest of times and places, etc. That’s why they seem to receive relatively minor punishments for behavior that would ruin the lives of the rest of us. There was a time a few years ago where it seemed like every member of the Cincinnati Bengals had been arrested for something. It became a running joke on the sports talk radio circuit. The details of the alleged crimes didn’t matter after a while.

When Vick was sentenced to 23 months in prison, many were outraged at the severity of the punishment. It was frequently weighed against the punishment given to Leonard Little, the St. Louis Rams’ defensive end who ran a red light and plowed into another car. He was drunk, over the legal limit and he killed the woman in the other vehicle. His punishment was four years probation and 1,000 hours of community service. He was suspended for eight games by the NFL. Little killed a woman and received no jail time. Vick killed dogs and ended up in Leavenworth for almost two years. People said, “Something’s wrong with that.” And they are absolutely right: The two punishments were way out of whack. But the problem wasn’t that Vick’s punishment was too severe; it was that Little’s wasn’t severe enough. How many of you even know who Leonard Little is, much less remember his crimes?

Just a few days ago, Nike signed Vick to an endorsement deal four years after they severed ties with him. Forgive and forget? Nike weighed the pros and the cons and they came to the conclusion that it makes business sense to have Vick out there on their behalf. Nike is banking on the fact that those of us who buy their products have forgiven by now (or don’t care). Nike can take the hit from those who, like me, will never buy another Nike product.

Just a few days ago, Nike signed Vick to an endorsement deal four years after they severed ties with him. Forgive and forget? Nike weighed the pros and the cons and they came to the conclusion that it makes business sense to have Vick out there on their behalf. Nike is banking on the fact that those of us who buy their products have forgiven by now (or don’t care). Nike can take the hit from those who, like me, will never buy another Nike product.

The Philadelphia Eagles had faith that their fans had forgiven Vick by 2009. He’s now the face of the franchise. The Ed Block Courage Award Foundation believed fans had forgiven Vick when they gave him their award the same year. The general consensus on talk radio is that he is forgiven (or, in some cases, there was nothing to forgive in the first place). The Humane Society has allowed Vick to participate in their End Dogfighting campaign. President Barack Obama forgave Vick, praising the Eagles’ owner for giving Vick a second chance. Obama said that “too many prisoners never get a fair second chance.” Then again, how many prisoners have PR teams and Tony Dungy vouching for them in the special, peculiar Tony Dungy kind of way?

I don’t think anyone has forgotten, though. Vick’s name will be forever synonymous with dogfighting. In the end, it seems that forgiving is more important and easier than forgetting. Forgiving is especially easy when it accompanies winning. Winning is very powerful force. Kobe Bryant has been forgiven since his rape charges in 2003. The eight years have helped, but the Lakers’ two championships really helped. Ray Lewis led the Ravens to a win in Super Bowl XXXV and was named its MVP. This was a year after his involvement (to whatever extent) in the stabbing deaths of two people. His past transgressions might even be forgotten at this point. When we talk about Lewis now, we talk about his place in the pantheon of football players, not his past.

I don’t think anyone has forgotten, though. Vick’s name will be forever synonymous with dogfighting. In the end, it seems that forgiving is more important and easier than forgetting. Forgiving is especially easy when it accompanies winning. Winning is very powerful force. Kobe Bryant has been forgiven since his rape charges in 2003. The eight years have helped, but the Lakers’ two championships really helped. Ray Lewis led the Ravens to a win in Super Bowl XXXV and was named its MVP. This was a year after his involvement (to whatever extent) in the stabbing deaths of two people. His past transgressions might even be forgotten at this point. When we talk about Lewis now, we talk about his place in the pantheon of football players, not his past.

Forgiveness does not require winning, though. Winning just makes it easier. What forgiveness should require is remorse, some sign that the transgressor knows the wrong in their transgression. Some people don’t care if he’s remorseful at all. Many people believe Vick is genuinely remorseful and these people are closer to Vick than I am. When he walked out of prison a free man, he had a goal to be back in the NFL. We had the expectation he would be back. We wondered what team would take that risk. Vick is back to making many millions of dollars playing football and many of us are back to cheering him on.

I have a hard time believing that Vick’s total lack of compassion can be overcome with a little less than two years in prison. I hear him say, “My daughters miss having [a dog], and that’s the hardest thing: Telling them that we can’t have one because of my actions.” That doesn’t show me that he learned anything or that he’s rehabilitated. It shows me there’s still a bit of a persecution complex lurking beneath the polished and prepared talking points.

It has been said that he paid his “debt to society.” I’m not sure what that means. But obviously many people do. If he continues to play as he did in the 2010 season, if by some miracle the Eagles win a Super Bowl, the percentage of people who forgive will increase. That’s how it works, for better or for worse.

It has been said that he paid his “debt to society.” I’m not sure what that means. But obviously many people do. If he continues to play as he did in the 2010 season, if by some miracle the Eagles win a Super Bowl, the percentage of people who forgive will increase. That’s how it works, for better or for worse.

So, do we sports fans forgive and forget too easily? If Leonard Little can slam into a woman while driving drunk and play in the Super Bowl less than a year later, the answer is yes. If it only takes four years to go from the most vilified athlete, possibly ever, to being the Comeback Player of the Year and making $20 million, the answer is yes. If the decision to forgive is in any way based on the success of the player, the answer is yes. And it’s not just the fans: The establishment, the leagues, the companies—they all forgive too easily.

A fellow contributor here commented, “America sure loves a comeback story, huh?” We do indeed. And Vick’s comeback is one we rarely see. His comeback is truly amazing. What that comeback signifies about sports fans, what it says about our society and what it teaches the kids that may look up to him, remains to be seen.